Ethertoff: experiments in real-time collaboration on writing and design

The tools to design publications reflect the divisions of labour used in the world of graphic design. When one starts to use tools for design that originate in another field, they bring along new ideas of how the work process is organised. This is the case when using web technologies like HTML and CSS for designing publications. A particularly exciting change is that the tools enable all kinds of new ways to work together.

Most Content Management Systems designed with the web in mind accord the designer the role of designing the template. In a traditional design workflow the designer has full control over the final output. With a CMS the designer switches positions, and takes a position earlier in the chain. They design a template in the hope that the content will fit with it.

Designers interested in pushing the boundaries of their tools will find Content Management Systems a fruitful area to hack. Whereas many fields of Software are dominated by commercial products from large companies, major web publishing tools have come about as grassroots efforts. Projects like Wordpress and Drupal are built on relatively simple technologies and feature a community-driven development. It seems possible then, to develop new publishing tools that re-imagine the role of the template and the division of labour implicit in it.

In this article we look at the experimental publishing tools created by OSP in developing web publishing platforms that re-imagine the collaboration process and the divisions it entails. In this case the designer is neither in final full control over the output, nor only involved in the initial template—there is a constant feedback loop between writing, editing and design. These tools go by the name of Ethertoff.

Collaboration Models in Design Software

Traditional design software offers a solitary experience. It takes a very organised design studio to manage a collaboration in inDesign, the most popular software for designing print publications. The first hurdle: collaborators must all own the same version of the program. Then, the publication is contained in one big binary INDD file. If two people change that same file, it is nigh impossible to consolidate these changes.

A publication created with HTML is contained in a series of text files. These text files are ‘plain text’: the most simple way a computer can store data. Plain text is readable by the most basic of text editing programs. Computer programmers have long had a (sometimes unhealthy) love affair with plain text, as it is the format in which they store their code. There is a huge amount of tools developed to deal with plain text, and especially interesting are these that enable collaboration. This means that designing publications in HTML and CSS allows designers to use a whole new set of tools.

One of these technologies that suddenly makes a lot of sense to use is Git. A very sophisticated program that is meant to track revisions of files, and allow people to work on their own version of the files after which these new versions can be merged back together in various ways. The advantage is that users can work on their own devices in their own private space, and synch the changes after.

There is another form of collaboration that is theoretically possible in Graphic design programs, but seldomly implemented: Real-time collaboration. Real-time collaboration is a method where multiple people are working on the same document at the same time. It is different from most other forms of collaboration in the sense that users can see each others updates directly. Google Docs is the most well known of such software, but an early and adorable incarnation of the paradigm is Etherpad. Like tellyou describes in ‘I like tight pants and Etherpad Or The Textarea Is A Lonely Place’, real-time collaboration is an addictive model that would feel in place in many web applications.

The Evolution of Ethertoff

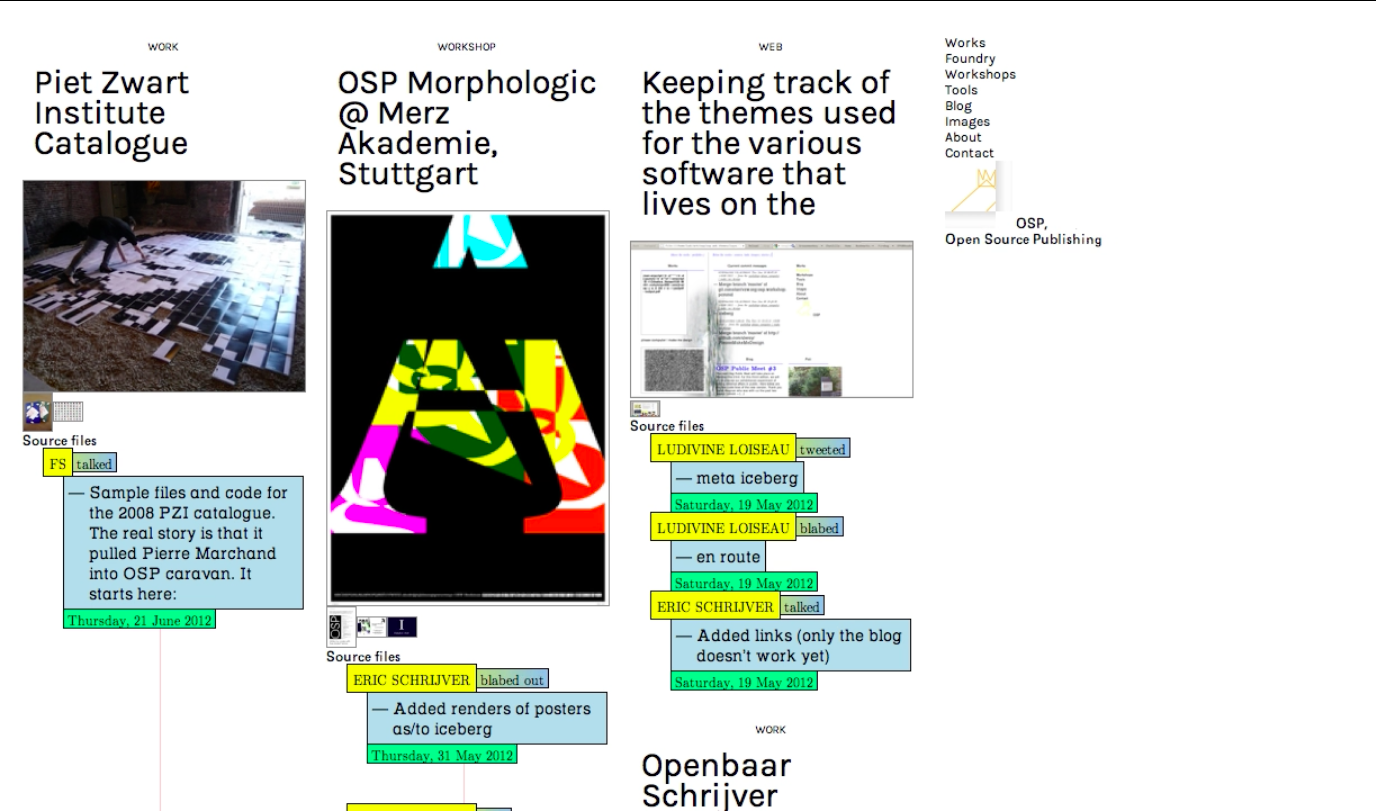

Graphical Design collective Open Source Publishing has long been using Etherpad to work together. Initially only for taking notes, but soon for the collaborative editing of web designs. As the style information for a website is contained in a CSS file (a stylesheet), collaboratively editing this file makes it possible to create mockups together.

The initial desire to use Etherpad for creating publications comes from a disenchantment with Wiki software. Wikis are, by definition, minimalistic collaboration tools that make it easy to create web content with multiple people. But the editing interfaces, often based on editing forms, lack the immediacy of Etherpad’s real-time collaboration—in which multiple users can actually see each other edit the text at the same time.

The project Ethertoff started out as wiki software that uses Etherpad’s direct editing capacities. Over time it evolved by letting users not only edit text, but the design as well. As a software it has been specifically used to develop publications, and it has evolved with each publication for which it was used.

Relearn

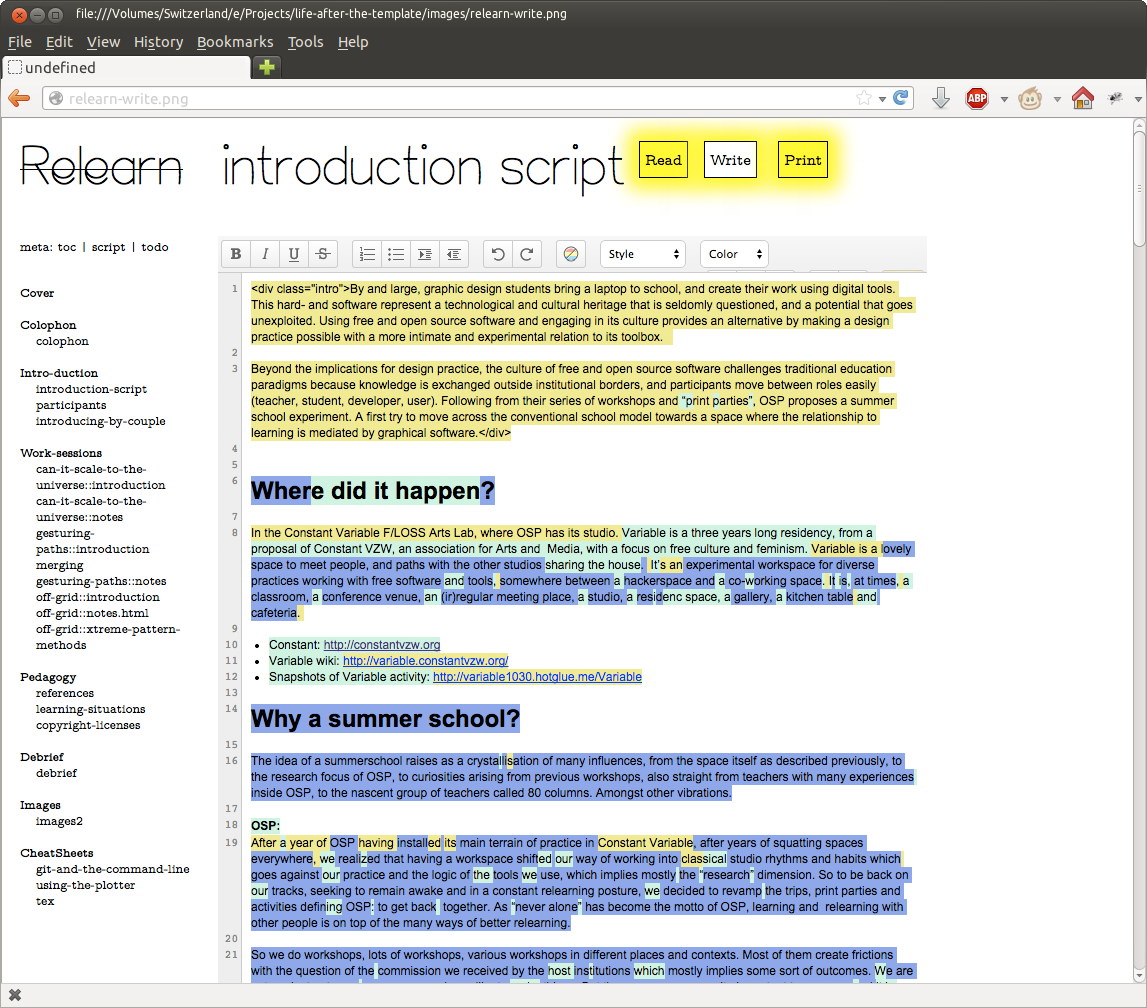

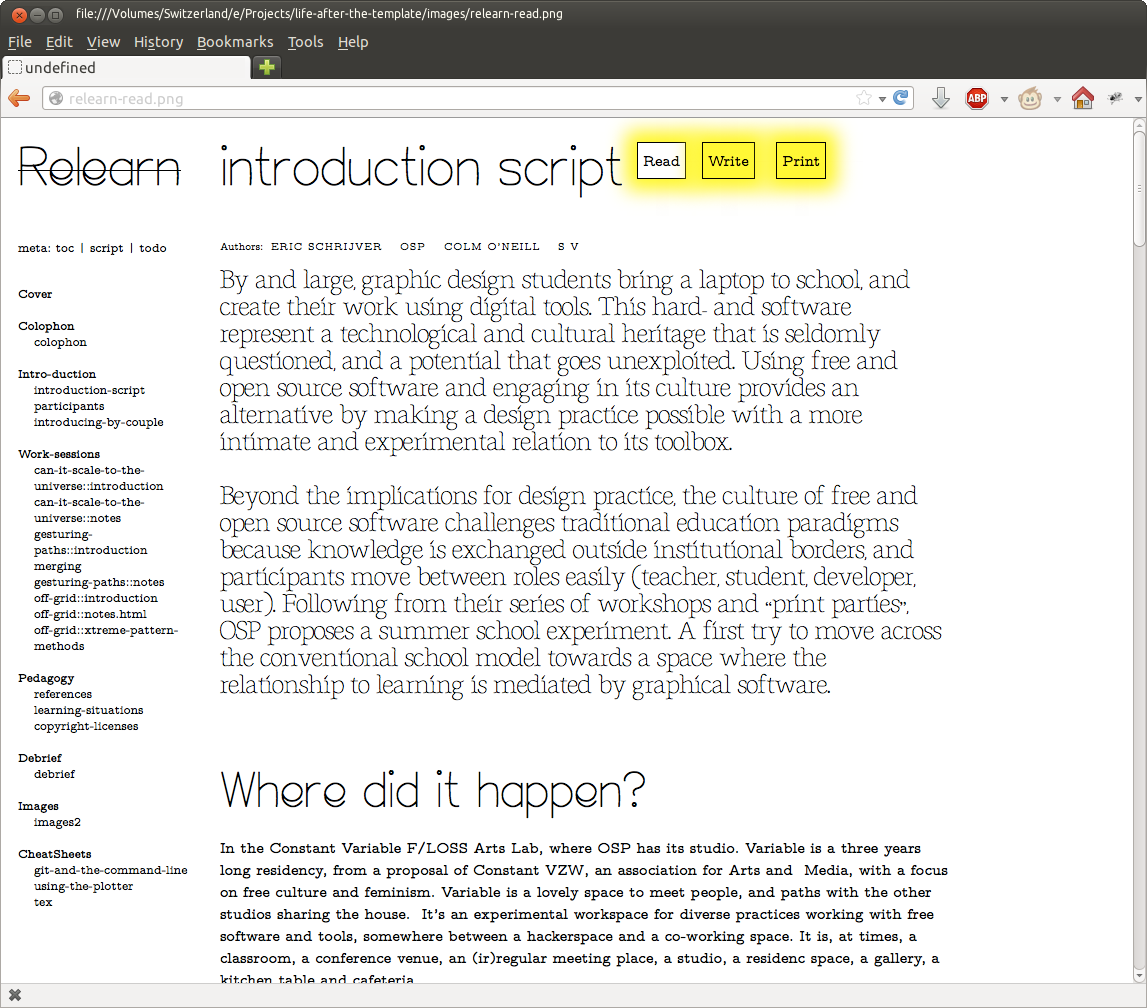

The first version of Ethertoff has been developed to create the publication ‘Relearn’. The requirements for Ethertoff were to provide for a fluid path from note-taking, to editing, to styling, to creating a printed publication. The OSP initiated Summer School Relearn is based on pedagogical experimentation: shifting roles and models of knowledge exchange. Ethertoff reflects this. Whereas the traditional publishing model is ordered sequentially, in Ethertoff all options are available all at once.

Such a flexible approach is bound to create conflict. One limitation that soon becomes apparent is that it becomes impossible, for better or for worse, to finish the publication. Authors and editors always feel like they can still change their texts at any moment. The potential for change allows editors to leave text in a state that they would not otherwise leave it in. This effect is heightened by the collaborative aspect, as editors feel like another editor might finish their job later.

Using the same tool for web and print output has a set of challenges of its own. On the web, one is used to seeing text with no or minimal copy-editing. Also, one is used to web platforms like Wikipedia where a ‘final’ version of a text does not exist. Once the publication shifts to the printed form, this becomes very different. Print has the connotation of finality. The linear nature of the book also suggests the possibility of a tension arc, whereas in a hyperlinked space all pages are created equal, and usually no fixed path is set between them. Reading the rough, multi-voiced, unfinished text typeset as a traditional book clashes with all the associations we have with the printed page.

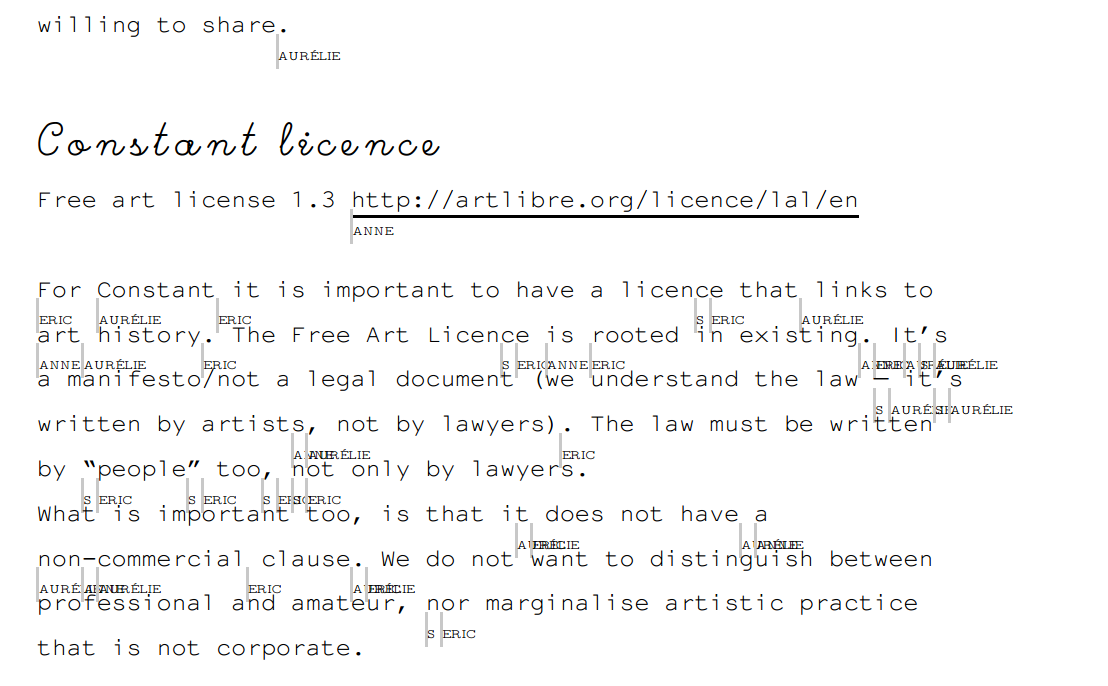

To resolve this conflict we tried to let the typesetting of the text reflect its origins. Etherpad uses background colours to delimit different authors. By default this information gets thrown away on export. We have kept it, and transformed it to a graphical form better fit for the laser printer. One can see which author contributed which part of speech, understanding the process by which the text has come about.

This version was developed by Eric Schrijver, with Stéphanie Vilayphiou. Design by Pierre Huyghebaert, Ludivine Loiseau, Samuel Rivers Moore, Eric Schrijver, Stéphanie Vilayphiou. At the Hackathon ‘Free Libraries for Every Soul’, Ludivine Loiseau and Eric Schrijver implemented the feature to edit CSS directly as a pad.

f-u-t-u-r-e.org

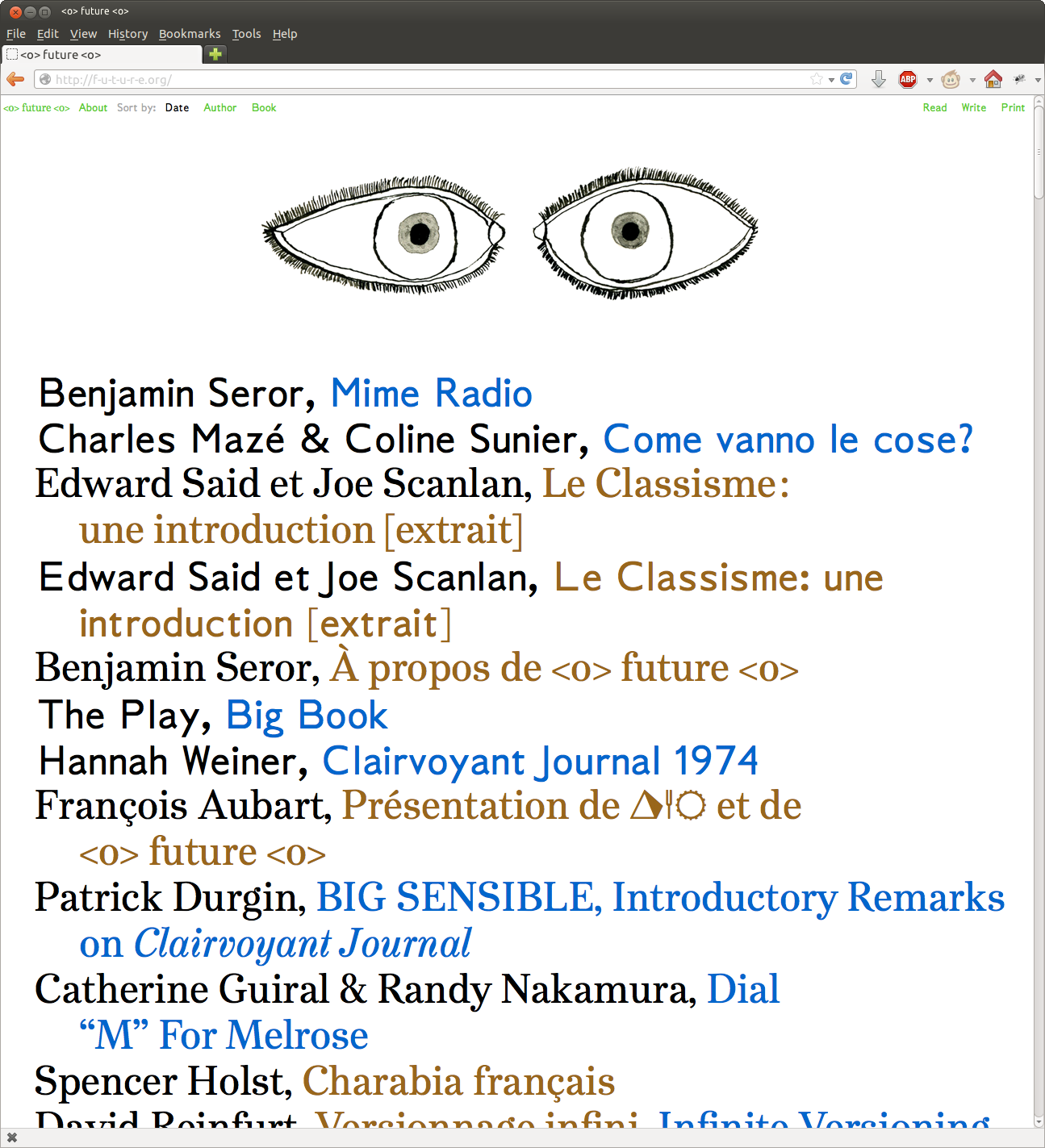

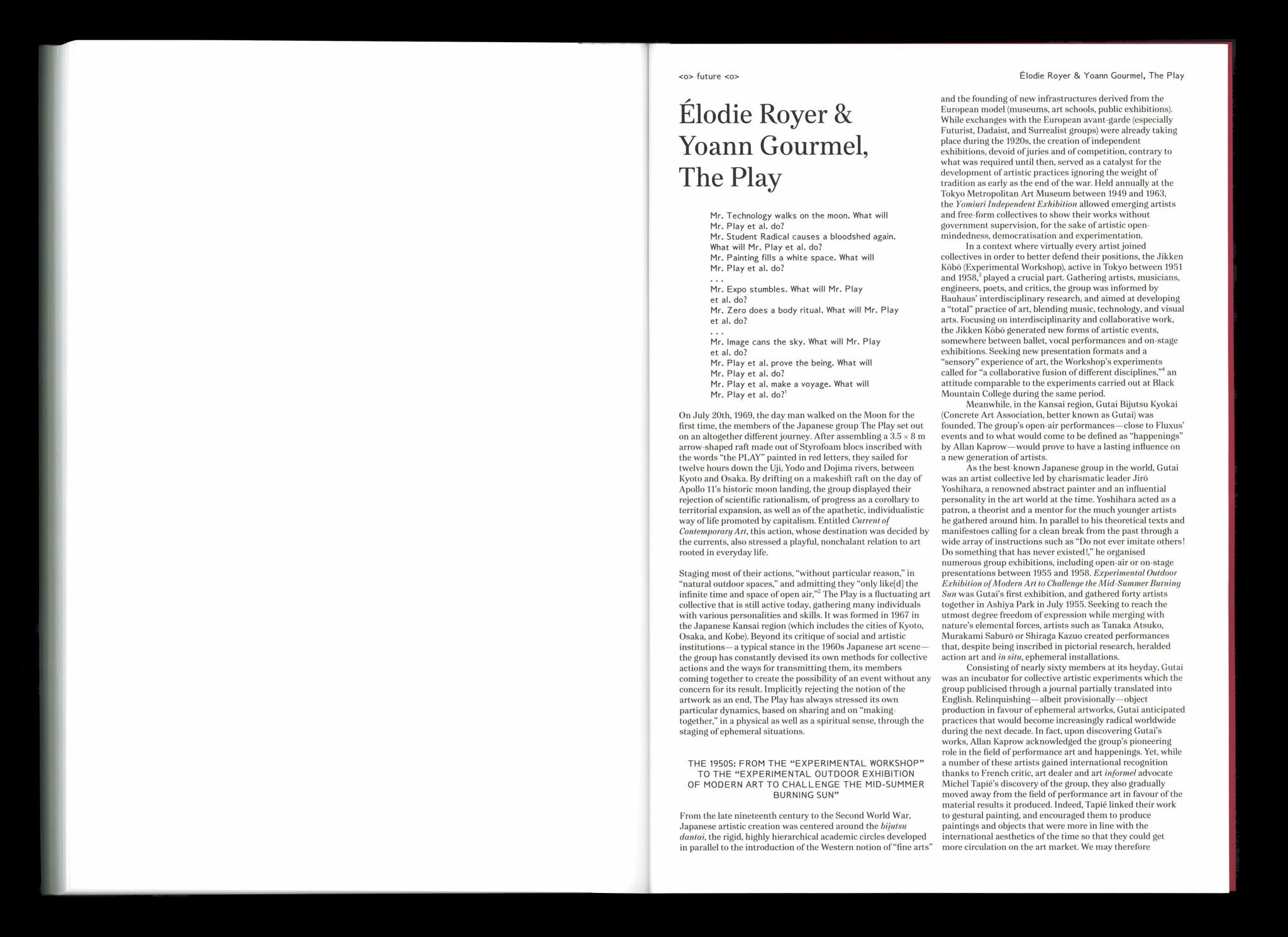

BAT éditions is a French art publisher producing among others the magazine ∆⅄⎈. ∆⅄⎈ features both new and re-printed texts on art and culture. An important role of the magazine is to make texts known to new publics: texts might come from outside the art field, they might be earlier texts rediscovered, or they might be translated from English into French or French into English. The issues of ∆⅄⎈ are exquisitely designed and produced in a relatively small printing run on a Risograph. To make these texts more accessible, BAT has decided to continue publishing online, with the platform <o> future <o>.

In contrast with the texts in Relearn, BAT’s texts are created following a rigorous editing process. Working with Etherpads eliminates much of the drudgery of sending Word files from author to editor and back again. Since launching f-u-t-u-re.org, Bat has been publishing a large series of texts online, and published two printed versions of longer articles, created with the tool.

Given the instability of Etherpad’s rich text features, Bat’s version of Ethertoff offers two alternative ways of styling text: with the minimal language Markdown, or by using pure HTML codes. Which method to use is determined by the pad’s url extension. This version of Ethertoff also allows the generation of indexes from metadata. Finally, it is integrated with the HTML2print project to give the editors more control over the print output.

The platform was commissioned by BAT éditions and financially supported by the CNAP. In addition, the Montpellier art centre La Panacée enabled a residency for OSP to collaborate more closely with BAT. Design by BAT. Developed by Alexandre Leray, Eric Schrijver and Stéphanie Vilayphiou.

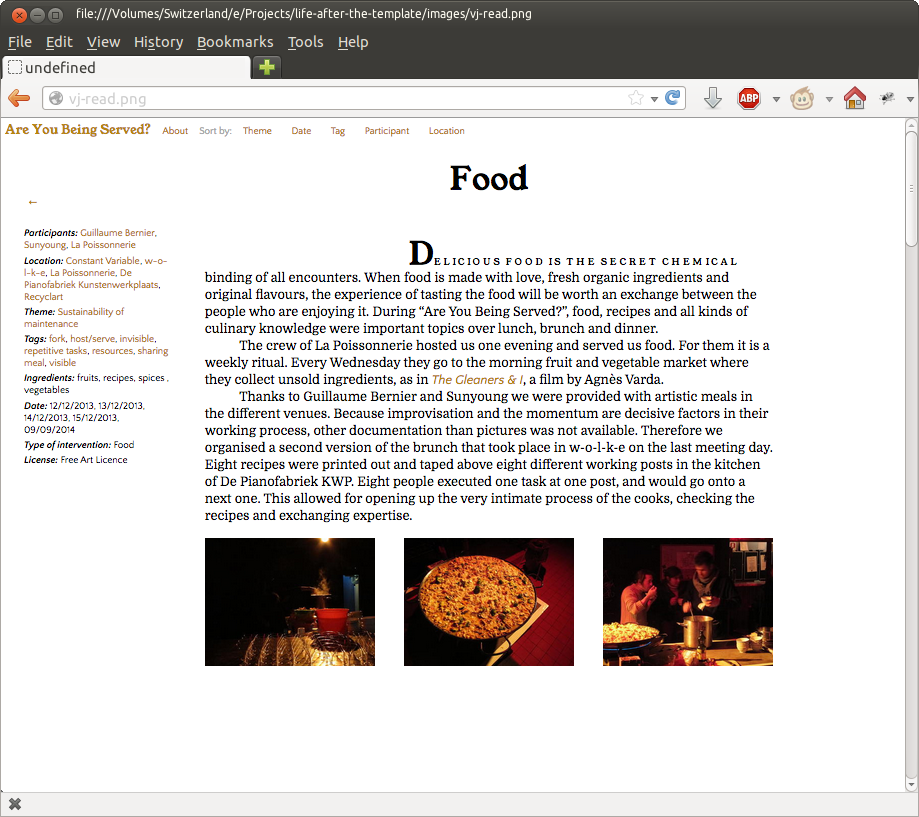

VJ14

The Media Lab Constant VZW i involved in the Relearn Summer School and had witnessed the process of its publication. For their own festival VJ14 they employed a somewhat different tactic: an initial group of notetakers worked during the festival, and several months later a group of editors worked to create the publication.

The main additions for the platform are: a better indexing function and the possibility to create a static archive of the generated publication.

Commissioned by Constant VZW. Design by Stéphanie Vilayphiou, development by Eric Schrijver and Stéphanie Vilayphiou.

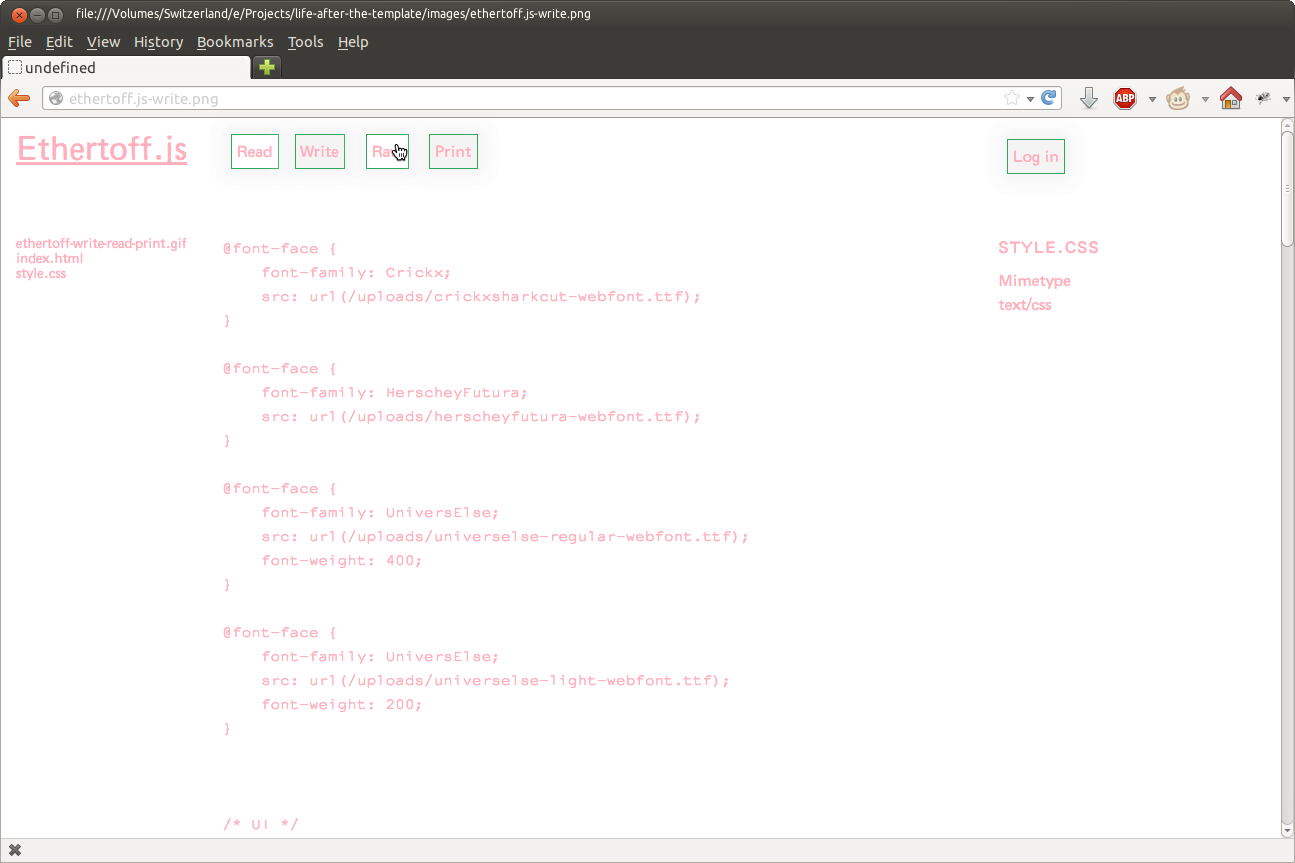

Ethertoff.js

Until now, the various versions of Ethertoff have been complicated to install. This is because they combined two different technology stacks: one Etherpad installation running on Node.js, and one wiki software built upon the Django framework, running on the Python programming language. Both parts need their own databases, and the synchronisation is sometimes brittle.

Supported by a Starter Grant from the Creative Industries Fund, Eric Schrijver rewrote the basis of ethertoff to work with the Node.js framework Derby.js. This framework comes with its own implementation of Operational Transformations, the underlying technology in Etherpad that manages to synchronise the changes across collaborators.

The new version has a tighter coupling to the file-system, allowing to initialise its database from a folder of files. It uses the CodeMirror editor to provide such amenities as syntax highlighting.

Christophe Clarijs, Thomas Laar, Lies Mertens, Wilco Monen, Eline van der Ploeg, Janine Terlouw used this version of Ethertoff to create a typographic interpretation of the evening ‘Beeldmakers’ at the Brakke Grond, Amsterdam. The concept: if form and content are both important in design, it makes sense if the documentation can use both these dimensions. This is made possible by creating live the stylesheet and the text of the documentation. Ethertoff.js proved to have its share of peculiarities still. A video of the process is included below:

To make Ethertoff perform better Eric has been in touch with the Open Source community surrounding Derby.js and Lever, the company in which the framework originated. He has visited the Lever offices in San Francisco and is currently planning the best way of continuing the development of Ethertoff.js.